Socialism Without Internal Social Dynamics Is Destined toCollapse

“What comes with crisis, goes with crisis.”

The historical emergence of real socialism has largelycoincided with the aftermath of major systemic crises. As Önder Apo underlined in his recent assessments from İmralı, the Soviet Union was born out of the structural collapse of thecapitalist order following World War I, while post–World WarII gave rise to state-centric socialist models such as China, Vietnam, and others.

Önder Apo’s reflections on these examples amount to a profound ontological critique of the mode of existence sharedby all past socialist experiences. These systems may havedeveloped internal dynamics, but they were primarily theproduct of external historical ruptures. That which is born of crisis is not fermented within the people — it is not rooted in the organic will of society, but rather takes the form of thestate, bypassing the moral and political foundations of thecollective.

Hence, every socialist theory that emerges as a response tosystemic crisis through external intervention tends to adopt a statist configuration, ultimately detaching itself from socialreality. In contrast, socialist theory and politics must arisefrom within — from the ethical, moral, and politicaltransformation of society itself.

From this perspective, the revolutions in question were not theresult of deeply developed social will, but of opportunisticresponses to moments of breakdown within the global system. For this reason, many such formations took on militaristic, statist, and centralized structures, shaped not by the internaltransformation of society, but by the immediate urgencies of war and power vacuums.

The common trait of these experiences lies in the fact that theywere not founded upon the long-term ethical and politicalorganization of society, but rather on filling the power voidscreated by crisis. Their revolutionary praxis focused not on internal social evolution, but on the tactical seizure of statestructures in moments of systemic fracture. What was lackingwas not strategy, but depth of relation with society’s memory, culture, and internal will.

Önder Apo’s statement, “what comes with crisis, goes withcrisis,” is not merely a historical observation, but an ontological critique concerning the epistemological, methodological, and existential dimensions of socialism.

No socialist formation that is not born from within society — from ecology, democracy, woman, culture, ethics, andhistorical consciousness — can produce lasting freedom.

This is why democratic socialism must not rely solely on crisisconditions, but must be grounded in social consciousness, moral-political organization, and the leadership of women. While periods of crisis and rupture may act as catalysts, theycannot be foundational. What is foundational is the moral-political will of society itself.

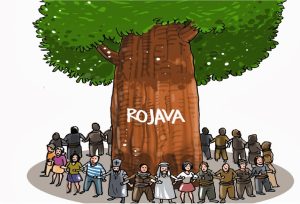

This insight also explains why today’s paradigm is beingconstructed around internal dynamics such as woman, society, ethics, ecology, and direct democracy.

Any socialist structure that arises outside of society’s internaldynamics may gain short-term strength, but will inevitablycollapse in the long run, for it fails to establish a genuineconnection with collective memory, with the peoplethemselves, and with values.

History offers numerous examples.

The Soviet system may have won the war, but it failed toeliminate the roots of inequality and could not establish peace.

The Chinese revolution armed its people and createdresistance institutions, but it could not liberate them.

Vietnam resisted imperialism, but as it became increasinglystatist, it distanced itself from its people.

These structures did not prioritize internal social evolution, but responded to war-imposed urgencies. They were born in crisis, but failed to transcend it. Once the crisis ended, theirhistorical legitimacy dissipated.

Önder Apo’s paradigm represents a critical rupture here:

True socialism does not emerge from crisis.

It is built through the ethical, cultural, and organizationaldepth of the people — through social consciousness, led bywomen.

Thus, social revolutions must not be based merely on theopportunities crises present, but on a profound shift in socialmentality.

Today, the conditions of the Third World War — a new global crisis phase — carry the risk of repeating the same illusion.

Any system built purely on the opportunity of crisis will, as in past examples, remain fragile.

A system established by crisis is destined to collapse by crisis.

Therefore, these historical experiences hold deeper meaningthan ever for all social, cultural, ecological, ethnic, andspiritual movements that claim to uphold a socialist theory andpolitics.

The new socialist line does not pass through the state, but through society and its self-administration;

Not through the party, but through moral-politicalorganization;

Not through production relations and political processes alone, but through the construction of a new social mentality.

It must be born not merely from crisis, but from the internalunity of truth and ethical organization.

The permanence of socialism lies not in its structures, but in the depth of its relationship with the people.

What emerges through relation, meaning, and organizationendures.

What arises from external rupture inevitably fades.

Socialism is not the child of external crises — it is the fruit of internal transformation.